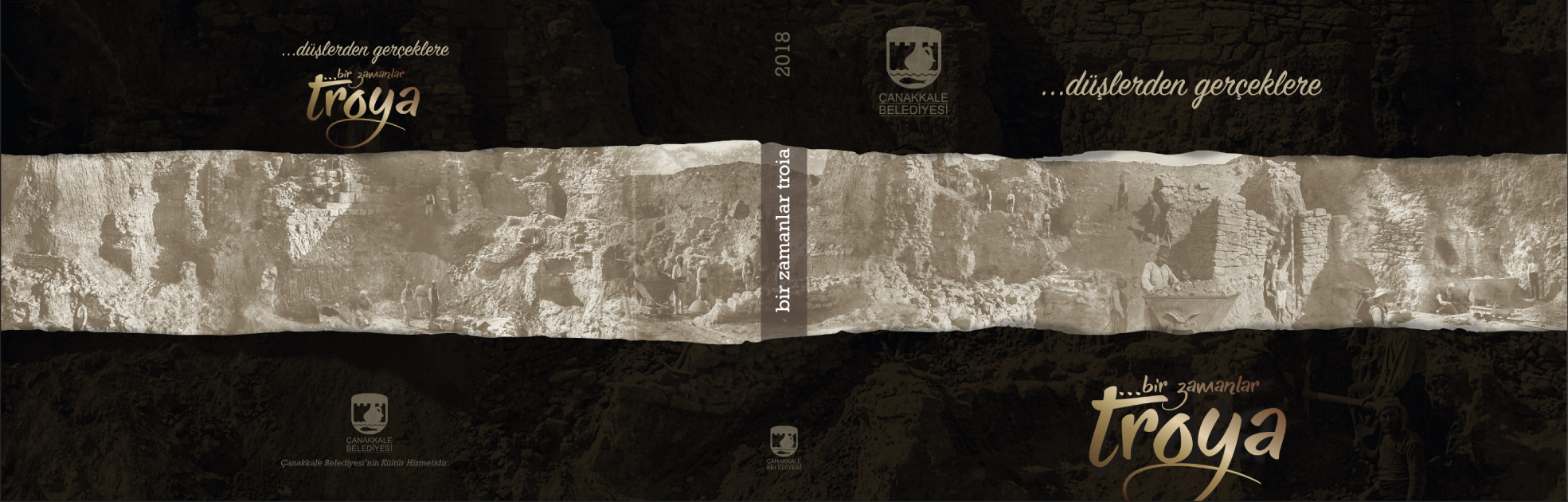

Memories from Troy

1872-1894

The city of Troy, which is the subject of Homer's epic poems, is located on the Asian shores of the Dardanelles, opposite the Gallipoli Peninsula. From the 8th century BC, the inhabitants of the Classical Period Ilion city, located at the westernmost point of a plateau about 5 km from the sea, believed that the city they lived in was Troy. This city was destroyed by a violent earthquake around 500 BC and was later abandoned. However, the name Troy continued to be mentioned in that region. Medieval travelers who visited the area believed they saw the ruins of Troy at various places along the coast. However, 17th-century travelers approached the question of where Troy was located more critically. Some began research by claiming that Troy was inland. The first identification of Troy's location was made in 1784 by the topographer Jean-Baptiste Lechevalier during research conducted by the French in northeastern Aegean. In the results of this research, it was claimed that the ancient settlement on the Ballıdağ hill above the village of Pınarbaşı, at the very edge of the Troy Plain, about 15 km northeast of Hisarlık Hill (Troy), was Troy. Lechevalier saw the river flowing under this hill, overlooking the Troy Plain, the islands, and the Dardanelles, as the Scamander; the stream formed by the Kırkközler spring as the Simois, and the four tumuli (burial mounds) on the hill as the tombs of the heroes of the Trojan War. Thus, according to him, the events described in the Iliad were proven by topography. This theory was accepted for about 100 years. However, in later research, engineer Franz Kauffer discovered a new settlement in 1793, closer to the sea, which the Turks called Hisarlık/Asarlık Hill. After examining the coins and inscriptions found on this hill, Daniel Clark, a mineralogist from Cambridge University, determined in 1801 that this was the classical period Ilion city. After this determination, for a while, Hisarlık Hill was accepted as the classical period Ilion city, and Homer's Troy was believed to be at Ballıdağ in Pınarbaşı. Nevertheless, some researchers argued that this view could not be correct with their critical approaches. The Englishman Charles Maclaren, in an article published in 1820, argued that the water flowing under the village of Pınarbaşı could not be the Scamander mentioned in Homer's Iliad; that in Homer's descriptions, Troy/Ilion was described as being between two rivers, and therefore Troy could only be at Hisarlık Hill. With this view, the classical period Ilion and Homer's Troy were placed in the same location. In fact, Homer also defines the city with two names in his epics, both as Troy and Ilion. Maclaren further developed this view and published it in detail as a book in 1863.

Frank Calvert (1828-1908) of the Calvert family living in Çanakkale, who was aware of Maclaren's views, conducted excavations in 1863 and 1865 on the land they bought at Hisarlık Hill. The results of Calvert's excavations, which showed a stratification belonging to very different and ancient periods, supported Maclaren's views; however, Calvert did not have the money to conduct broader and more comprehensive excavations. In 1865, Frank Calvert wrote a letter to Ch. Newton, the director of the British Museum at the time, stating that Hisarlık Hill could be Troy and that if he were helped, he could prove this with extensive excavations. However, he did not receive a positive response. At such a critical time, the paths of the wealthy German Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890) and Frank Calvert crossed in Çanakkale.

Unaware of J. Maclaren's Hisarlık/Troy thesis, H. Schliemann conducted excavations for a few weeks in 1868 at Ballıdağ in Pınarbaşı to find Troy. However, the data he obtained did not convince him. When he missed the ship to Athens via Çanakkale, he had to stay in Çanakkale for two days and thus met F. Calvert. Calvert told Schliemann about Hisarlık Hill and the excavations he had conducted. He mentioned Maclaren's thesis and publications about Troy. Believing what was told, Schliemann decided to excavate at Hisarlık Hill. In 1869, Schliemann presented his travels in Greece and the Troad as a doctoral thesis to the University of Rostock (Germany), writing that he had discovered Troy alone. His thesis was accepted. A year after his Troad trip, Schliemann, now a historian-archaeologist with a doctorate, came to the region in 1870, this time to conduct excavations. Excavations began at Hisarlık Hill, but since he did not have permission and due to the landowner's complaint, the excavations were stopped. After long efforts, he obtained permission, and the Schliemann excavations, which continued intermittently until his death in 1890 (1871-73; 1878-9; 1882; 1890), began in 1871. The treasure find, which Schliemann found in 1873 and mistakenly dated about 1200 years earlier as the "Treasure of Priam," caused a great sensation in the world at that time. Schliemann first smuggled these treasures to Athens and then to Germany. After the Second World War, the treasure finds, taken to Russia as war booty, are still exhibited in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow.

After Schliemann's death, the excavations were carried out by his friend, the German architect Wilhelm Dörpfeld (1853-1940), in 1893-94. Dörpfeld had participated in Schliemann's excavations since 1882 and was the first to apply many techniques not commonly used in excavations at that time at Hisarlık/Troy. For example, for the first time, a mound was divided into squares with a coordinate system, and all excavations were documented in detail with a grid system. Again, for the first time, researchers from different fields of expertise participated in the excavations. The documentation of Schliemann's excavations, which began in 1872, with sketches and photographs became more systematic with Dörpfeld's participation. The work completed by Dörpfeld in 1894 formed the basis for later studies. For example, when the American archaeologist Carl W. Blegen (1887-1971) resumed excavations at Troy between 1932 and 1938, he used the same coordinate system. After a fifty-year break, the new period excavations, which are still ongoing, were carried out by Manfred Osman Korfmann from the University of Tübingen, who continued the same system by developing it from 1988 until his death in 2005.

The photographs in the book not only present a portrait of the workers working in the region during the excavations but also show Schliemann and Dörpfeld during their work.

Rüstem ASLAN